Research-Driven Literacy Instruction

The Science of Reading

Table Of Contents

Educators, policymakers, and researchers have fiercely debated how to approach literacy instruction for decades. These debates have shaped everything from classroom practices to teacher training, often creating deep divisions over the best approach. A fundamental question is at the heart of the conversation: How does the human brain learn to read?

1. What is the Science of Reading?

The Science of Reading is not a trend or a passing educational movement—it is the result of decades of cognitive science, neuroscience, linguistics, psychology, and education. These fields have collectively uncovered how the human brain learns to read and what instructional practices are most effective for all learners, particularly those who struggle.

The Science of Reading confirms that:

- Reading is not an innate skill—it must be explicitly taught.

- Phonemic awareness and phonics instruction are critical for helping students decode words.

- Fluent reading depends on rapid word recognition, which develops through systematic practice, not guessing or memorization.

- Reading comprehension builds on a strong foundation of decoding skills, vocabulary knowledge, and background information.

Ready to change how you approach reading instruction? Our on-demand Science of Reading offers proven strategies for phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension that will help all students succeed. >> Learn More and Register

2. A Look Back at How We Teach Reading

For over 150 years, educators have debated the best way to teach children to read. Classroom methodologies have shifted in response to research, policy changes, and evolving educational philosophies. From the early Alphabetic Method, which relied on rote memorization of letters, to the more recent Structured Literacy approach grounded in cognitive science, each method has influenced how students learn to read—and, in many cases, how they struggle.

The chart below provides a comparative overview of major reading instruction methodologies over the past 150 years.

%20(1800%20x%201300%20px)%20(2)-png.png?width=2200&height=1800&name=List%20Comparison%20Table%20Infographic%20Instagram%20Post%20(1500%20x%20100%20px)%20(1800%20x%201300%20px)%20(2)-png.png)

3. Balanced Literacy vs. Structured Literacy Instruction

Starting in the 1950s, educators, policymakers, and the public became increasingly divided over how children should be taught to read.

The publication of Rudolf Flesch’s Why Johnny Can’t Read (1955) ignited a national debate, arguing that the widespread shift from phonics toward look-say and whole-word methods was failing children.

Flesch’s argument resonated with parents and policymakers, many of whom were alarmed by declining literacy rates and the number of children struggling to read.

In response, advocates of whole language approaches pushed back, arguing that reading is a natural process that children acquire much like spoken language—through exposure, context, and meaning-making rather than explicit instruction.

By the 1960s and 1970s, this philosophy had gained traction in many schools, shifting the focus from phonics-based decoding to a meaning-centered approach that encouraged children to rely on pictures, context clues, and memorization to recognize words.

Despite growing concerns from linguistics and cognitive science researchers, whole language remained dominant through the 1980s.

However, by the 1990s, the weight of scientific evidence made it increasingly difficult to ignore the importance of systematic phonics instruction.

Research from scholars like Jeanne Chall, Marilyn Adams, and Linnea Ehri provided compelling evidence that skilled reading depends on the ability to decode words using phonics rather than guessing based on context.

The National Reading Panel (2000) further solidified this conclusion. After reviewing hundreds of studies, the panel reported that systematic phonics instruction was essential for teaching children to read alongside phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies.

What is Balanced Literacy?

Despite research highlighting the importance of phonics, balanced literacy—a modified version of whole language that included some phonics instruction without making it central—remained the dominant approach in many classrooms.

What is Structured Literacy?

By the 2010s, the International Dyslexia Association (IDA) formally introduced Structured Literacy to describe an explicit, systematic approach to reading instruction grounded in decades of cognitive science research. Unlike balanced literacy, which often encourages students to rely on pictures or context clues, Structured Literacy teaches students to break words down into their component sounds and decode them systematically.

By the 2020s, the Science of Reading movement had gained widespread momentum, pushing states and districts to adopt research-backed instruction that prioritizes explicit phonics, phonemic awareness, and evidence-based reading practices.

Today, the debate is no longer about how children learn to read—the research is clear. The real challenge is ensuring this knowledge translates into practice in every classroom so that all students receive the instruction they need to become proficient readers.

%20(1)-png.png?width=1080&height=1500&name=List%20Comparison%20Table%20Infographic%20Instagram%20Post%20(1080%20x%201500%20px)%20(1)-png.png)

4. The Science Behind How Students Learn to Read

While reading is a complex process for all students, decades of research-based literature outlining evidence-based strategies for reading instruction already exist to guide educators in the right direction.

Both The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Rope are foundational science of reading research tools for educators.

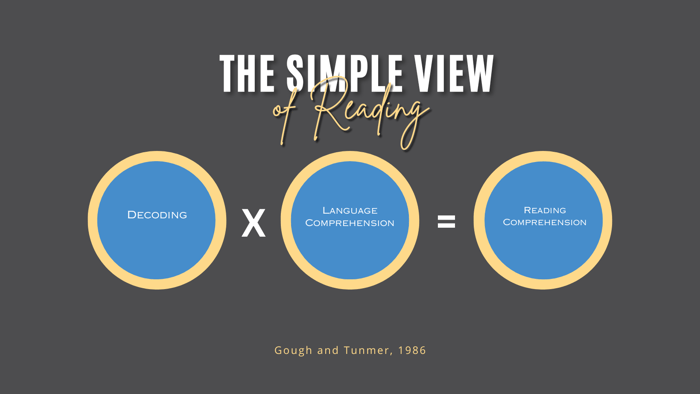

The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986)

The Simple View of Reading was introduced by researchers Gough and Tunmer in 1986 to reconcile ‘The Reading Wars.' Gough and Tunmer sought to eliminate hierarchical thinking that prioritized decoding or comprehension as a higher priority over the other rather than interdependent skills that together build reading comprehension.

This research proposed that reading comprehension is the result of two fundamental skills:

- Decoding (word recognition) – The ability to accurately read words.

- Language comprehension – Understanding spoken and written language.

If either skill is weak, reading comprehension suffers. This model underscores the importance of explicit phonics instruction alongside language development, challenging approaches focusing solely on comprehension strategies without ensuring students can decode words effectively.

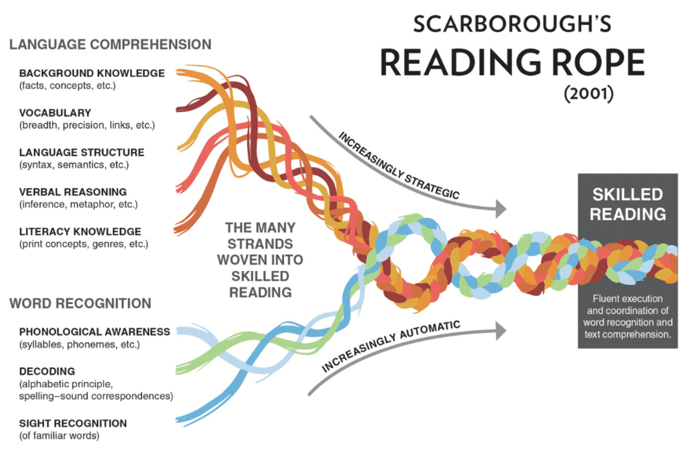

Scarborough's Reading Rope (2001)

Dr. Hollis Scarborough expanded on the Simple View of Reading by introducing the Reading Rope, which illustrates how multiple strands of skills intertwine to create skilled reading. These strands fall into two categories:

Word Recognition Strands:

- Phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition (which rely on decoding, not memorization).

- Language Comprehension Strands: Vocabulary, background knowledge, and verbal reasoning.

The Reading Rope model reinforces that fluent, skilled reading requires strong decoding and comprehension skills, which must be explicitly developed over time.

In 2001, the model was published in the Handbook of Early Literacy Research. Reading teachers immediately saw how useful it was, and it became a staple for educating new teachers and parents alike.

For teachers of English reading, this provides a visual reminder of the complex components of reading and the number of things that must be taught to achieve success.

Why This Research Matters

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence supporting phonics-based instruction, many classrooms still rely on outdated, disproven approaches, such as cueing strategies (guessing words based on pictures or context) and leveled reading restricting access to challenging texts.

As states and districts work to align instruction with the Science of Reading, it’s critical to recognize that this movement is not about preferences—it’s about what research has consistently shown to be effective for all learners.

By embracing evidence-based instruction, we can ensure that every child has the opportunity to develop strong reading skills, breaking the cycle of literacy struggles and opening doors to lifelong learning.

5. Bringing Structured Literacy to Schools

The Science of Reading movement has gained significant traction in recent years, pushing reading instruction away from outdated, ineffective methods toward evidence-based practices. As states, school districts, educators, and parents increasingly recognize the urgent need for change, a national effort is underway to align reading instruction with what research shows works.

This movement is driven by three key forces: policy shifts, teacher training reforms, and grassroots advocacy from parents and journalists.

Policy Shifts: States and Districts Requiring Phonics-Based Instruction

In response to overwhelming research supporting Structured Literacy, many states have begun passing legislation mandating phonics-based instruction in schools. These laws aim to phase out ineffective strategies, such as three-cueing (which relies on guessing words based on pictures or context), and ensure that all students receive explicit, systematic phonics instruction.

Some of the key policy changes include:

- Banning cueing strategies and leveled reading programs that encourage guessing instead of decoding.

- Mandating the use of evidence-based reading curricula aligned with the Science of Reading.

- Revising state literacy standards to prioritize phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

- Requiring universal screening for reading difficulties (including dyslexia) to identify struggling readers early.

As of 2024, more than 40 states and the District of Columbia have enacted literacy laws that align with the Science of Reading, marking a significant shift away from Balanced Literacy.

For example, In Maryland, a 2024 reform requires third-grade students who do not meet state reading standards to enroll in supplemental reading support programs before advancing to fourth grade. This policy aims to address early literacy challenges and ensure students receive the necessary support.

The challenge now lies in implementation—ensuring that schools and teachers have the resources, professional development, and support necessary to effectively transition to Structured Literacy.

Teacher Training Reforms: Equipping Educators with the Right Tools

One of the biggest barriers to change has been how teacher preparation programs have traditionally taught reading instruction. Many educators were trained in Balanced Literacy methods, often with little to no formal instruction in phonics or how to teach decoding skills explicitly.

As states and districts shift toward the Science of Reading, there is a growing push to retrain teachers so they can confidently implement Structured Literacy in their classrooms. These efforts include:

- Overhauling teacher certification programs to require training in phonics-based instruction.

- Providing professional development in Structured Literacy for current teachers, helping them move away from cueing strategies and leveled reading.

- Expanding access to Science of Reading-aligned instructional resources so teachers have the tools they need to apply their training effectively.

Tennessee’s Early Literacy Success Act mandates that teachers receive training in phonics-based instruction and that schools adopt curricula grounded in the Science of Reading. Other states, including Mississippi, Colorado, and North Carolina, have implemented similar measures, showing promising improvements in literacy rates.

As more states recognize the critical role teachers play in closing the literacy gap, efforts to support and equip them with evidence-based training will continue to grow.

The Role of Journalists and Grassroots Movements

While research has long supported explicit phonics instruction, much of the momentum behind the Science of Reading movement has come from parents, advocates, and investigative journalists who have brought the issue into the public spotlight.

One of the most influential voices in this movement has been journalist Emily Hanford. Her investigative reports, including the widely shared "Hard Words" (2018) and "Sold a Story" (2022), exposed how flawed reading instruction had left millions of children struggling.

Her reporting resonated with parents who had spent years watching their children struggle with reading, despite attending school regularly. Parents of children with dyslexia, in particular, have become powerful advocates for change, demanding that schools adopt research-backed reading instruction.

The combination of policy changes, teacher training reforms, and parent-led advocacy has fueled a nationwide movement to make evidence-based reading instruction the norm, not the exception.

6. Take Action in the Science of Reading Movement

The Science of Reading has provided us with clear, research-backed methods for helping all students become proficient readers. As we move forward, it's critical to put this knowledge into practice. At Lavinia Group, we are here to guide you every step of the way.

What You Can Do:

-

Sign up for our On-Demand Science of Reading Course or Workshop: Our courses and workshops provide practical, research-based strategies for teachers, instructional coaches, and school leaders. Get the tools you need to implement Structured Literacy and improve reading outcomes in your classrooms.

-

Explore our RedThread Literacy Curriculum: Built on the latest Science of Reading research, RedThread offers a comprehensive, systematic approach to teaching reading that ensures every student develops the foundational skills needed for success.